Report of the Flight from Jarek According to Records

by Michael Schmidt, Wilhelm Heinz and Nikolaus Schurr

by Inge Morgenthaler

translated by Sieghart Rein

Jarek as of 1941:

Jarek, situated about 15 kilometers northeast of Novi Sad on the main road Novi Sad-Betschej, was an exclusively German community with approximately 2000 inhabitants. When, in 1941, the war between the Axis powers and Yugoslavia broke out, only a few Jarek men got their enlistment into the Yugoslav military; however, not all could enlist anymore, because the Yugoslav army found itself in disbandment in the shortest time. Indeed, of the Jarek Germans seven or eight hostages were to be arrested and carried off on Palm Sunday, April 6, 1941; they, however, were warned in time and could avoid being arrested.

Thousands of soldiers of the Yugoslav army passed through Jarek on their retreat. The front doors of the houses in the main street had to remain open, so that camp followers and soldiers had the opportunity to spend the night. No acts of sabotage were committed by the Germans, however smaller units of Yugoslav soldiers left their weapons behind voluntarily, while larger units retreated unhindered toward Novi Sad.

The village was occupied by Hungarian units without a fight. The Jarekers had, as nearly everywhere in the German communities of the Batschka, expected that German troops would enter the Batschka. Thus the Hungarian troops were not at all cheered and welcomed as liberators, for which the Jarek administration was reproached on part of the Hungarians at every opportunity. Encroachments by the Hungarians did not materialize in Jarek; the German Gemeinderichter (burgomaster) Nikolaus Schurr succeeded even to retain the previous administrative personnel at the establishment of the Hungarian sovereign authority. To be sure, the notary of the community, Johann Böhm, was transferred to Schowe, but Adolf Arnold came to Jarek as notary instead. Postmaster and teachers, all sons of the community, were taken over by the Hungarians. The means of communication of the community administration remained German; the officials wrote the applications in Hungarian.

Those born in 1920 were mustered into the Hungarian army. The following age groups did service in the German army.

In summer of 1944 all men to the age of fifteen had ultimately reported for duty. Since the local government feared that partisan attacks could occur, an armed village militia was set up, which had to guard the village at night. This precaution was, of course, concealed from the people of Jarek, because otherwise “there would have been an end to the peace” as Nikolaus Schurr expressed it. There were no encroachments of the partisans, as in other Danube Swabian villages, as in Srem, for example.

The village administration had been ordered to bring in the harvest despite a lack of manpower. Even the Hungarian airmen, who had set up their landing strip on the Herrschaftswiese (meadow), helped harvest the maize and wine. In September 1944 Novi Sad was heavily bombarded. Subsequently, a stream of refugees poured from the city into the small village, because they felt safer “in the country.” Middle of September, while the Jarekers still pursued their usual work, the first refugees from the Banat came into the community. They mainly lodged only for one night and moved on.

By that it became clear to the Jarekers what was in store for them. Especially those who remained in the village mostly older farmers were not happy with the prospect of being evacuated. The village had about 9000 yokes of fields. The 3000 yokes maize had practically been harvested at the beginning of October. 600 railroad cars and additional 35 railroad cars of the harvest of 1943, stored in the village, were no longer bought by “Futura,” the state Hungarian trading company for agricultural products, so that many farmers owned hardly any ready cash for the barest necessities of life with which they were to prepare themselves for the flight.

A German military command was located in Jarek. Its commandant (Colonel Böhme, according to all accounts) drew the local authorities’ attention to the critical situation and to the dangers to life and limb in case of remaining in the home village in sufficient time. Thus a systematic preparation for the flight was initiated for the predominant part of Jarekers that resulted — in contrast to many other Danube Swabian communities — in a somewhat orderly process of evacuation. It did not take place in panic. According to a statement by Teacher Heinz, only 54 persons remained.

Preparation for the Flight:

After it was obvious that one could not remain in the village, appropriate measures were taken. The blacksmiths in the village got the wagons for the escape ready. Old hoops were cut through and placed over the wagons, which were yet widened with boards at the sides. With the help of “Fruchttücher” (large cloths of woven hemp linen) and old carpets they were then “roofed.” The horses were shod and the hoops of the wagons were tightened. The women provided for ample provisions. Whoever had not yet butchered [the hogs] made up for that now. Ham, bacon, and sausage were made or meat was roasted and was put into enameled “Schmalzstenner” (containers for lard storage) with the lard. Also a supply of bread and dry “Pogatschen” (round mostly salty bakery) was baked. The people wanted to have enough food with them for at least the first few days. No one knew, of course, how the journey into uncertainty would proceed and, above all, not how long it would last. On the bottom of the wagon the crates with clothing and linens were stowed, the bedding was placed above them, but, according to the old Danube Swabian custom, the better linens and the good clothes were left in the closet; worn-out work clothing was put on for the flight. Many went yet to get family trees, baptismal and marriage certificates at the church; some also packed documents, testimonials, credentials, report cards, etc. and the “Heimatbuch” (book of the history of the village), not surmising that just these things should prove themselves as a priceless remembrance.

The Flight:

On Friday, October 6, 1944 at 11 o'clock at night everyone was called upon to assemble the next day for the departure. But actually on October 7th tremendous confusion prevailed on the main road because the German infantry was ordered to the Tisza-front, while units with heavy vehicles were retreating in the opposite direction. Finally, at two o'clock in the afternoon, Colonel Böhme ordered Burgomaster Nikolaus Schurr to take over the command of the trek and to set off towards Novi Sad without delay. Thus approximately 300 wagons left the village that day. As the column started to move, the church bells rang out and Teacher Wilhelm Heinz played the organ. He concluded the last organ playing in the empty church symbolically with the hymn “Entrust all your days and burdens.” In Novi Sad there was again an air-raid warning and the streets were jammed with military vehicles. Thus the Group Schurr arrived in Futok late at night. Since there was no overnight accommodation to be found, the wagons were arranged on the so-called “Krautwiese” (cabbage -meadow). The next day they continued on. Some villages through which the Column Schurr went, were still inhabited, others had already been abandoned, as, for example, Miletitsch. Here the refugees could rest once more and feed their animals before continuing on.

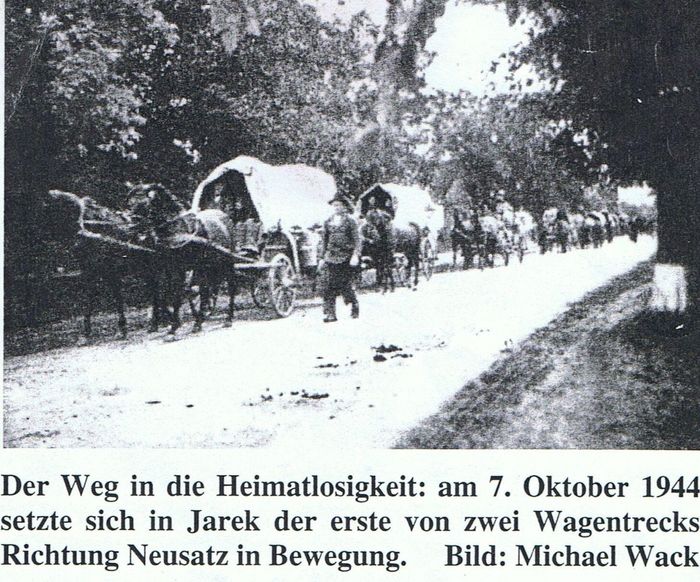

The road into homelessness:

On October 7, 1944 the first wagon trek of two wagon treks started out

in the direction of Novi Sad.

Photo: Michael Wack

On Sunday, October 8th, 140 wagons once again left the village. The command of this trek was entrusted to Johann Schollenberger, who in the community had held the office of “Waisenvater” (a man in charge of orphans). This group also arrived late at night in Futok. The Futoker themselves were now in the act of preparing for the flight, and there was enormous confusion in the village.

Thus within two days altogether 440 wagons, pulled by approximately 1000 horses and 14 tractors, left the community of Jarek. Since both treks were too large, the desire to form smaller units became evident, because that way it was easier to find accommodations for the night and to procure feed for the horses. Thus a partial group from Schollenberger's trek managed to get across the Danube by ferry near Mohacs. In doing so, a Jarek woman was knocked into the Danube by her shying horses, and she drowned. The treks which did not want to entrust themselves to the unsteady ferries in Bezdan and Baja, continued on in forced marches to the bridge in Dunaföldvar, constantly driven by the fear the Russians could arrive there before the treks. Here prevailed total chaos because everyone wanted yet to cross the Danube to get to safety.

An eyewitness reports:

“The soiled road sign indicated only a few kilometers till the next village Dunaföldvar and the Danube. This short way was nearly like the one to the kingdom of heaven; many crowded and pushed their way forward on the narrow path. It became constantly more difficult for our column to make headway, into which others had already mixed themselves, although soldiers endeavored to direct the traffic according to their best efforts. German army wagons moved towards the west, just like we, Hungarian Honveds strived in a diametrically opposite direction towards the east, and right and left in the fields cannons were in positions, at which soldiers were lying around apathetically. Actually, here was certain security, but in the air lay a stillness which struck one as uncanny. One also was told that air-raid alarm had been given. The stillness drew one the more agonizingly into its spell, the closer one got to the bridge. Suddenly faster headway was made in good order and with an anxious heart. In the distance there was the whining of engines in the air. Despite the passing trucks and cars this noise was clearly and decidedly different; it had something droning and threatening all at once. We were a short distance from the bridge, when the first bomber squadron arrived. At great altitude their silvery fuselage and wings could be recognized. Now just forward as fast as possible! Pressing forward, forward at any price, perhaps it will work out well yet again! Horse-drawn Hungarian artillery move towards the left bank of the Danube; we moved towards the right bank. We were now on the asphalt of the bridge. Below us the clayey waters of the Danube rolled along lazily and apparently slowly. Soon our crossing had succeeded, and we were in Transdanubien. Having arrived there on safe ground, one could heave a sigh of relief. But we had hardly gone 500 meters when strafers nosedived at the endless columns like hawks out of a cloudless sky. Precautionary measures had been taken for such eventualities. The soldiers displayed their Hungarian temperament and prowess in utmost perfection by firing as if by magic. Of the approaching airplanes they had transformed half of them into scrap metal in a few moments. Except for several injured at other columns, there were no victims to be bemoaned. The column came to a stop at the attack of the escorting fighter aircrafts. The people fled to the nearby maize that had not yet been harvested. Several could even shelter their horses there, others did not even have time to help their old people, who sat on the wagon, get down. God was merciful to us. Except for several overturned wagons, at which the horses had shied, our trek got off with only having a scare. The wagons were put back into working order and then we continued at a walking pace toward the northwest, for our journey was certainly not yet at an end. (loc. cit., pp. 266, 267)

In Jarek, however, approximately 70 fully packed wagons had been left standing in the street on October 8th, because they had no team of horses. They belonged to families of craftsmen and poorer families, whose husbands had enlisted. An officer of the Waffen-SS made Teacher Wilhelm Heinz responsible for the evacuation of these families and did not let him leave with his family. The army ordered trucks to Jarek. The refugees had to reload their most necessary belongings, were brought to the Novi Sad ship landing stage and loaded into a barge. Their journey went upstream on the Danube until Mohacs. There they were put into railroad freight cars and finally taken by way of Pécs (Fünfkirchen) and Sopron (Ödenburg) to Vienna. After having survived an airstrike, which did not claim any casualties among the Jarekers, the journey continued on to Munich. Here the separation of the transport into all directions took place. These people, too, experienced a terrible odyssey, until they finally found a transitionally temporary stable place to stay.

The Group Schurr moved along the south shore of the “Plattensee” (Balaton) in strenuous day marches, then toward the northwest. On November 20th they reached Sopron. Approximately half of the remaining trek, including horses and wagons could be loaded into train freight cars, because the station chief turned out to be an acquaintance of Nikolaus Schurr and he wanted to do him a favor. The train brought them to Silesia via Vienna and Czechoslovakia. In Gellendorf in the vicinity of Breslau they found a place to stay.

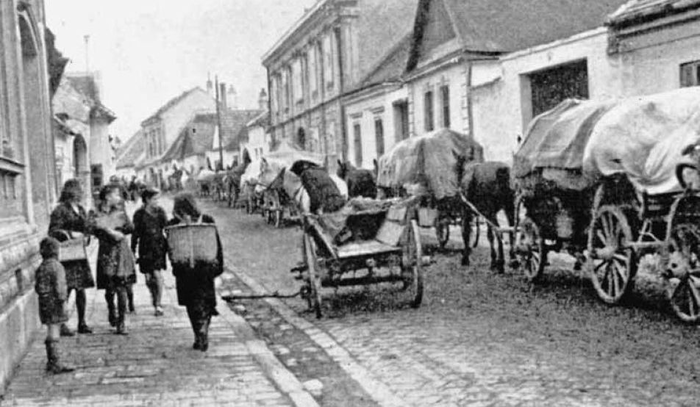

Refugee trek from the Batschka on the way to Silesia in November 1944

moving through the town Ödenburg (Sopron)

Source: Michael Boehm: “Unsere Heimatvertriebene,” p. 14

(This could have been the Jarek trek)

The second section of the Group Schurr was now commanded by Franz Renner, who had lived in the Spitalgasse. This trek got just before Vienna where its horses and wagons were confiscated by the military. A part of them remained in Vienna. The other part was also transported by railroad to Silesia. The same happened to a further Jarek group near St. Pölten. After their horses and wagons had been taken away from them, they were brought to Lower Silesia in the District Goldberg-Haynau and the District Hirschberg in two days and nights.

In January 1945 the Jarekers along with the Silesians had to take flight again, since the Russians in the east came constantly closer. The Group Schurr, which still encompassed about fifty horse-drawn wagons, moved, under the greatest exertion through the snow-covered “Riesengebirge” and through Czechoslovakia into the “Oberpfalz” (Upper Palatinate). In order to remain somewhat unmolested by the Czechs, who found themselves in liberation frenzy and wanted to take revenge on everyone who was German, this trek made blue-white-red flags, so that the refugees would be regarded as Yugoslav citizens. The core of this group moved through the Upper Palatinate to the Danube at Regensburg, because they still hoped to get to the old Homeland from there. The Group Renner, which was evacuated from Silesia by railroad, only by chance eluded the fiery inferno of Dresden. Its train arrived in the afternoon of February 12th in Dresden, prior to the bombing and due to the overcrowding of the railroad station was not permitted to enter anymore. The train continued farther into Czechoslovakia till Austria. There they learned about what had happened during the night of February 13th in Dresden.

One part of the Jarek groups from Lower Silesia succeeded yet in time in the evacuation into Germany. They arrived by train in Lower Bavaria. The other part was overtaken by the Russians. In summer 1945 they were to be transported back to Yugoslavia. The railroad cars with the belongings were uncoupled in Pressburg and exposed to plundering. The Jarekers found themselves shortly after completely robbed clean and destitute on a platform in Vienna. They found temporary mass quarters and work at an estate near Vienna.

404 soldiers from Jarek had enlisted. After Wilhelm Heinz had left, 54 persons remained in Jarek. Therefore roughly 1540 Jarekers must have fled. The rate of those who fled is thus around 97%, surely one of the highest among the Batschka-Germans. During the flight and in the Lager 106 persons died and 5 are missing. The enormous exertions of the flight have scarred the people. Most of them lost nearly all they had during the flight. They carried all their belongings in two suitcases. Those who until the end had fled with horse and wagon were able to save several commemorative pieces and keepsakes. Despite all their adversity the Jarekers were yet very fortunate. Had they remained at home, many of them would have perished in the camps. Of the 54 who remained at home, over half died in the camps.

The Jarekers, besides their houses and about 9000 yokes of fields which they owned on various “Hottern” (precincts), left behind nearly the entire harvest of 1944 besides 3200 fattened hogs, 2220 heads of cattle, and 7500 heads of poultry. Of the horses 500 were requisitioned by the state and the military, the remainder was required for the evacuation. Of machines left behind: 14 threshing machines,250 reaping binders, ten motor-run and 300 hand-operated maize huskers, 1500 plows, 1200 maize chippers, 1200 roller harrows, harrows and floats, 350 sowing machines,300 cereal windmills, three large cereal cleaning machines and 30 fertilizer spreaders. In addition, the Jarek Germans owned a mill, a silo with a 40-railroad-car capacity, and a generating station that also supplied the town of Temerin and finally a co-operatively controlled hemp factory, in which all hemp farmers participated. In addition, they owned over 100 “Salaschen” (summer farms) in the Jareker precinct and surrounding precincts.

After the village had been abandoned by its inhabitants, only the military remained in the village until the end of October. But even during the army's presence the houses and barns were plundered, the machines carted away, the entire village was emptied out.

Already on December 3rd the Germans from Budisava, who did not flee, were brought into the empty village, after that the Germans from the other villages in the South-Batschka. Jarek became one of the worst internment camps: a death camp for the aged, the sick and the children. Until 1946 of the over 15,000 camp inmates approximately 6500 people died of starvation, illnesses and abuses, with 900 children among them. But that is another story. The mill owner Georg Haug from Jarek, who broke off his flight in Futok and returned to Jarek on October 13th, drastically describes the plundering of his home village and also the life in the “Lager” (camp). (See: www.hog-jarek.de: “Das Lager”.)

We Jarekers have lost everything, but could save our lives nevertheless. The planning and execution of the flight and the request of the German military to leave the village, contributed substantially to it. In other villages in the Batschka and especially in the Banat the leaving of one's village was prohibited under penalty. There, far more Danube Swabians lost their lives. Regrettably not all flight experiences could be described here, for every family has its own story of the flight.

A more detailed report of the experiences described above is in the reprint of the Heimatbuch of 1937: “Batschki Jarak-Jarek,” which was published in 1958 on pages 238 to 276.

Our Flight from Hungary to Silesia

by Theresia Haug, née Renner

Our trek, commanded by Nikolaus Schurr arrived at the end of November in Sopron (Ödenburg).

Michael Schmidt wrote the next paragraph in the book Batschki Jarak-Jarek (Reprint of 1958), pp. 271–272. “The largest part of the Group Schurr has come until Sopron. The exertions of the last days, forced marches without sufficient rest had worn down man and animal. A ray of hope appeared when it was reported that there was the eventual possibility to board a train with horse and wagon. After a lengthy back and forth such a possibility was discovered by accident, and about half the wagons with horses and other accessories were loaded. This came about with the help of a Hungarian station chief, who happened to be an acquaintance of Burgomaster Schurr and who wanted to be appreciative toward him by assembling a freight train. It was the last one which brought refugees to safety in this manner. The journey went via Vienna and through Czechoslovakia to Silesia.”

After several days of riding on the train we arrived in Silesia. We were deloused, although we did not have any lice. We got to Gellendorf with several families. The village is situated north of Breslau. At first we got lodging at an estate. I can still remember an occurrence: We were sitting around a large table and ate our ham and bacon which we brought from home. Children looked in at the window; they said “These people eat bacon without bread.” But we had bread with it. We were lodged in two small rooms, and our horses and wagons were put up at a “Domäne “(manor). The lady of the manor invited us on a Sunday. She gave me two books.

In Gellendorf we spent the first Christmas abroad. After the holidays I was enrolled in the secondary school in Obernigh; my report card was left there. I got to know a nice girl, Gisela Wegner. My brother got to be far from us to Thammühl in the Sudetengau at a “Gymnasium”(classical secondary school). Why were we brought to Silesia? Hitler wanted to enlarge his Greater German Reich toward the east (this madness); we Danube Swabians were to be settled in the Ukraine. We lived in the vicinity of the train station; many trains went to the east with banners “The Wheels Roll for Victory.”

The Flight from Silesia to Bavaria

The flight from Gellendorf began at the end of January. The order came; the refugees have to move to the west. We packed our things, fetched our horses and wagons and had to take leave again from these dear people, who had taken us in.

On the first day we drove over the Oder, our overnight accommodations were a large room. We sat around a table and slept sitting, bent forward on our hands. Suddenly Uncle Schurr fainted and fell to the floor. The next day we continued to Rohnstock. We rested; brakes were put on our wagons there. We had a difficult journey ahead of us over the “Riesengebirge”, “Iser Mountains” and the “Erzgebirge”. In Schreiberau we met our great-grandmother with family. Often we spent the night in stables. In the “Erzgebirge” we met with a kind reception, and were allowed to sleep in white beds. In Binsdorf near Tetschen-Bodenbach we could recuperate from the exertions over the mountains. In the last winter of the war, 1945, it was very cold; I had chilblain at the heels; we also met prisoners, who were on foot, guarded by soldiers. Binsdorf was 60 km from Dresden. The day after the heavy air-raid, on February 14, 1945, there were scraps of paper in the air. Days after, we heard of the Bombing of the city.

Our journey continued to Dux – Brueck – Komotau. Before we reached Eger we searched for accommodations for the night; the people did not want to take us in. I yelled, “The same should happen to you.” They took us in then. Now I can understand; they were tired of having to constantly put up people. Near Eger we drove over the border into the “Oberpfalz”(Upper Palatinate). In Kössing in the vicinity of Vohenstrauss we got lodgings. In May the war was at an end; the people hung white sheets out the windows. The Americans drove into the village with their Jeeps and tanks; on the radiator they had German soldiers sitting. For me it was like the end of the world; I wept bitterly; our entire hope for a final victory was of no avail. In June we continued on in the direction of the Danube Plain; on the way we met my brother Juri; He, too, had got through safely.

The leader of our trek, Nikolaus Schurr, had led us well for many kilometers through many dangers; I want to express my thanks to him here. In Moosham near Regensburg we had found a home for several years. There my father returned from Russian captivity.

We thank God for His protecting hand.